Washington used to worship Silicon Valley. Few things made politicians’ hearts beat faster than the bipartisan love for big tech. Silicon Valley was building the future. Government’s role was to offer compliments and get out of the way.

Recently, however, the mood has shifted. Both sides of the political divide seem to be awakening to the possibility that letting the tech industry do whatever it wants hasn’t produced the best of all possible worlds. “I have found a flaw,” Alan Greenspan famously said in 2008 of his free-market worldview, as the global financial system imploded. A similar discovery may be dawning on our political class when it comes to its hands-off approach to Silicon Valley.

But the new taste for techno-skepticism is unlikely to lead to meaningful reform, for several reasons. One is money. The five biggest tech firms spend twice as much as Wall Street on lobbying Washington. It seems reasonable to assume that this insulates them from anything too painful in a political system as corrupt as ours.

But beyond that obstacle lies another: Russia. Without Russia, Washington wouldn’t be talking tough on tech. But Russia is also the worst possible way to understand what’s wrong with the internet, and how we might begin to fix it.

Making Russia the whipping boy for the problems of platforms like Facebook won’t produce a constructive political conversation about how to make the internet more democratic. Instead, it will probably make the internet worse – by accelerating the erosion of our digital civil liberties in the name of national security without doing anything to challenge Silicon Valley’s power over our lives.

We should welcome the new techno-skepticism, but not if it comes wrapped in a new cold war.

There is no doubt that Russia played a role in the 2016 presidential election. Almost every week, new disclosures help clarify the nature of that role.

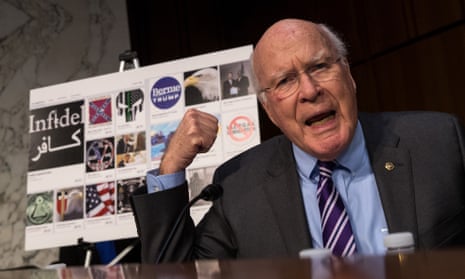

On the subject of Russian social media influence, however, the rhetoric far outpaces the reality. During recent congressional hearings, Senator Dianne Feinstein called it “a cataclysmic change” that marks “the beginning of cyber warfare”. Hillary Clinton recently claimed that it belonged to a broader Kremlin-coordinated offensive that amounted to a “cyber 9/11” – in other words, the digital equivalent of a terrorist attack in which nearly 3,000 people died.

Putting aside the irony of American politicians complaining about election interference, given our own rich history of manipulating and dismantling democracies around the world, this language is untethered from the facts. The latest disclosures center on the Internet Research Agency, a Kremlin-linked company known for running propaganda operations for the Russian government. According to statements provided to Congress, the Internet Research Agency distributed more than 131,000 messages on Twitter, uploaded more than 1,000 videos to YouTube, and published posts that may have reached as many as 126 million users on Facebook.

These numbers may seem large, but they’re not. The volume of content flowing through social media feeds is immense: on Facebook, Americans saw a total of 33 trillion posts from 2015 to 2017. And the amateurish quality of the Internet Research Agency campaign seriously compromised its effectiveness – a quarter of its posts were never seen by anyone. As for Twitter, the company reports that Russia-linked election tweets made up less than 1% of all election-related tweets between September 2016 and November 2016.

This doesn’t exactly add up to a “cyber 9/11”. But it’s not just that Russian social media influence wasn’t especially “cataclysmic”. It’s also that the Internet Research Agency used the platforms precisely the way they’re designed to be used.

As Zeynep Tufekci has pointed out, the business model of social media makes it a perfect tool for spreading propaganda. The majority of that propaganda isn’t coming from foreigners, however – it’s coming from homegrown, “legitimate” actors who pump vast sums of cash into shaping opinion on behalf of a candidate or cause.

Social media is a powerful weapon in the plutocratization of our politics. Never before has it been so easy for propagandists to purchase our attention with such precision. The core issue is an old one in American politics: money talks too much, to quote an Occupy slogan. And online, it talks even louder.

Unfortunately, the fixation on Russian “cyberwarfare” isn’t likely to bring us any closer to taking away money’s megaphone. Instead, it will probably be used as a pretext to make us less free in other ways – namely by justifying more authoritarian incursions by the state into the digital sphere.

The signs are already here. As part of the inquiry into Russian interference, Feinstein demanded that Twitter turn over a number of its users’ private messages. This is an alarming move, especially in light of a recent federal court order that gives prosecutors access to Facebook accounts used to organize the 20 January anti-inauguration protests.

The tragedy of 9/11 has long been weaponized to justify mass surveillance and state repression. The myth of the “cyber 9/11” will almost certainly be used for the same ends.

What we sorely need is popular mobilization from below. We need to impose sharp limits on political advertising – both online and off – to keep paid propaganda out of our public sphere. We need to demand democratic control of the platforms whose vast surveillance apparatus makes us easy and profitable prey for misinformation. And we need to put state power in the service of strengthening our digital civil liberties, not shredding them.

We also have to come to terms with the fact that America’s wounds are largely self-inflicted. One can acknowledge the evidence of Russian influence while also recognizing the deep domestic roots of our national catastrophe. Russia didn’t singlehandedly produce the crisis of legitimacy that helped put a deranged reality television star into the White House. Nor did it create the most sophisticated machinery in human history for selling our attention to the highest bidder.

It’s odd to blame Russian trolls for the destruction of American democracy when American democracy has proven more than capable of destroying itself. And rarely is it more self-destructive than when it believes it is protecting itself from its enemies.